Technology and product design challenges of building hardware and cameras

I often get asked how and why I decided to get into designing and selling hardware. I also get asked how our cameras are so good as in ‘what specifically makes them better than other solutions?”

So I thought I’d give you some insight into what it takes to invent and design new technology in general. Then in the next article I’ll explain how we here at Mosaic went through the process and how we chose the components and features that we did.

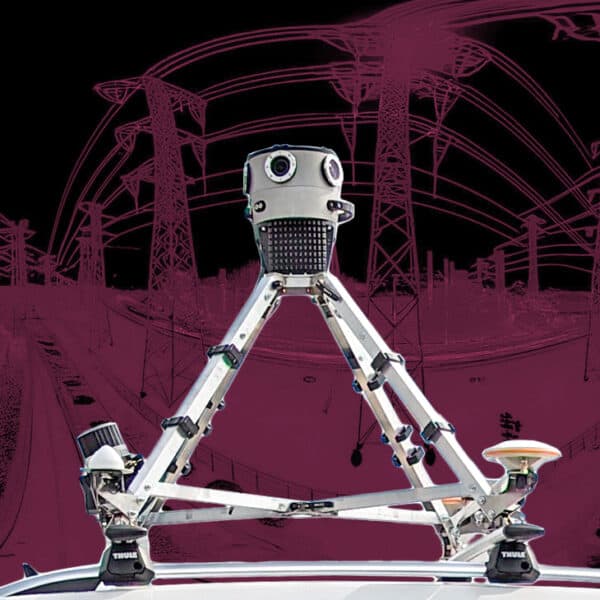

It’s been many years since I expanded from doing photography to working on building actual camera hardware. Mosaic has been shipping our flagship mobile mapping camera, the Mosaic 51, for a few years now, after having spent several years prior actively prototyping and testing internally.

In this post I’d like to talk about why some products are better than others and how products get invented and designed in the first place.

What’s involved in the invention and design process?

Building cameras requires many different disciplines and a lot of requirements and trade-offs.

- component selection

- systems design

- mechanical engineering

- electrical engineering

- firmware engineering

- software engineering

- optical testing and benchmarking

- User interface design

- User testing

- Etc. etc.

are just some of the parts needed to build a prototype product.

And that’s only the prototype! Getting from prototype to a mature product that is being physically manufactured at scale is another journey, requiring even more engineering, testing, verification procedures, and more.

How do things get invented?

So, how do you go about designing a new product in the first place? It depends on what kind of product it is. Some product designs are solved and have been perfected for decades or centuries. The bicycle, the toaster (well maybe not centuries), the sandal, scissors.

Sure, there is still room for some slight, incremental improvement to be made on these things as we improve materials, science and techniques. But I can certainly imagine that a thousand years from now, if humans are still around and still eat bread, they will have toasters that look like the ones we have been using since 1949.

Cameras that we use today (phones excluded) are sometimes incredibly similar to the very first SLR cameras in their user-facing design. Can you guess which of these two cameras is from 1959, and which is from 2020?

Obviously if you turn the cameras around, the Fujifilm XT4 (2020) on the right has a display, while the Nikon F (1959) does not… but if you gave the XT4 to my grandfather, he could most likely use it.

It’s also interesting to note that cameras went through at least a couple of decades when they didn’t usually look like the one on the left, and the camera on the right is very specifically designed to be similar to the older one, because it was actually a great solution.

Some of the biggest problems in the world are design problems

Despite what many believe,the design of products is not an act which commences with an idea, and then is executed with a design that is the best possible one for the user. Many decades went by with people putting a roll of film into a camera and taking lots of photos, before the Nikon F (the first ever SLR) was invented.

Product design is an iterative process which, for economic reasons, usually results in crude products entering the market, as soon as they are usable and reliable enough to meet a need better than the existing way. Subsequent iterations are made over a product’s life span, sometimes spanning decades, with a feedback loop between the users and the design/engineering teams. Eventually products can make abrupt evolutions when they are disrupted by new people with new ideas (The Innovator’s Dilemma).

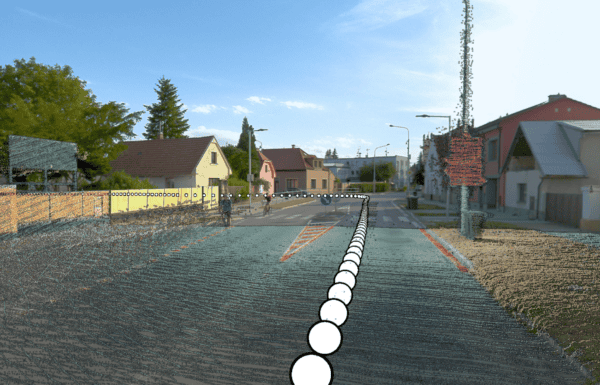

Anyway, there are certain things that are possible today which were not really feasible in say 1970. For example – mapping the world with 360º cameras – capturing hundreds of thousands of images a day, creating seamless 360º images plus detailed and accurate 3d models of the same places, all precisely positioned on the surface of the Earth within a few centimeters!

Just because it’s possible to do this, doesn’t mean that it is easy. Technology is one thing, turning that technology into a product which creates enough value for people to actually pay for it is something else. Products which “just work right” don’t just magically appear, usually.

In the case of motion-picture 360º cameras, outside of the gigantic unwieldy devices made throughout the 20th century (such as the Disney Circle-vision),

the first ever self-contained, portable 360º camera is widely considered to be this thing,

created by Dan Slater in 1992. (Unfortunately the link to the original page about this is dead, and it’s not on the Wayback Machine either)

It took until 2013 when Ricoh launched the Theta that the world had an actual mass-produced product that could take 360º photos.

2013 is not long ago in terms of a product category, and I would say that it is not long enough for that “perfect design” for 360º cameras to have emerged. It just takes a long time for the designers and engineers to talk to the people using the devices, and iterate, improving the problems that can’t be found without using the product.

There was no technological reason why this toaster from 1909

Could not have looked more like this toaster from 1949:

(Note: here is a must-watch video about how this toaster is much cooler than today’s toasters)

So even if we have all of the technology, we don’t necessarily know what the design should really be (even if the technology has already existed for decades) and it might also be impossible to spend the money on designing such a highly evolved product from the start.

I hope this demonstrates to you that many of the great problems in the world are design problems, not technology problems.

Engineers can solve technology problems and bring us new technologies. Designers and inventors have to figure out how to put these new technologies together into something new!

Design and technology are good friends, but they have different things to solve.

There might be a technology that comes into existence, but it takes a while for people to think of how to arrange that technology into a product that is successful: for example, the internet was around for decades before Google, Facebook, or Amazon became what they are today.

At this point it’s also worth noting that software, by virtue of it having zero marginal cost in terms of distribution and updates, allows this iteration at a speed and scale that is not possible with hardware – hence the “software is eating the world” idea.

So, let’s come back to mapping the world with 360º cameras. It’s a fairly new activity, and it has been pretty expensive to do, in terms of equipment cost, labor, data management and all related post processing tasks, and so on.

In terms of what actual machines are used to map the world, there have not been many choices, and there have been even fewer choices of devices that are designed specifically for this task.

Who even wants to design such a camera anyway? The market is small, and it’s such a complex product!

Lots of new products come about by someone who wants to “scratch their own itch” so to speak – if someone has a problem and finds a way to solve it for themselves, there can be a personal passion in the matter that is hard to match.

At Mosaic, our itch is that it is too difficult to map the world using the devices that have been available up until today. Even if you have a tool that can be used for this task, the actual result might not be very good. So our motivation in the last several years has been to solve this dilemma. And we are.

Addressing NOT having ‘the right tool for the job’ dilemma

Some of my colleagues have told me that I say this a lot, “you have to have the right tool for the job.”

For example, the Ladybug camera, while it has been a successful product, is both designed for generic usage (it doesn’t have a specific task in mind) making it unsuitable in certain respects in terms of robustness. It also does not offer a sufficient resolution for many basic kinds of imaging tasks that could be possible (reading signs at a certain distance, seeing cracks in the road, etc.)

Another example is the NCTech camera; while being designed more specifically for mapping the world, does not always offer the reliability that allows users to use the product in confidence. It’s infamously known for being quite ‘buggy.’

Besides actually designing a product that actually offers the necessary quality and reliability, there are of course lots of other things to consider:

- How to deal with heating and cooling

- How to deal with the storage device

- What should be the arrangement of the lenses

- What about the GPS?

- What about the connectors?

- Should we make it waterproof?

- How waterproof?

- What if I want to connect something else to the camera and have everything synchronized correctly?

Issues facing designers and engineers

These are all only the user-facing issues. Of course there are lots of other issues in electrical engineering and software engineering, there are tradeoffs to be made and things to fix. As a product design iterates, it amasses technical debt, sometimes more and sometimes less, depending on the circumstances and the team involved.

Designing a 360º camera presents a lot of additional challenges compared to designing a single sensor camera, both in terms of electrical/mechanical/software engineering, as well as optics, handling, power, heat, user interface, and so on.

Even the basic image characteristics and requirements in building a multi-sensor 360º camera are more challenging, because when you’re mapping a city or a street, you will ALWAYS have very bright objects and very dark objects in the scene that is captured by all the imagers; with a regular camera is this not always the case.

The optical characteristics of the lenses we use need to achieve a specification that is stricter than other cameras, both in terms of MTF (resolution) and the lens distortion which is calibrated by our team for each and every camera module that we use to build our camera systems.

How mobile mapping cameras add an additional level of difficulty

Mobile mapping is as much about photography as it is about metrology – after all, many of our customers need images to inspect objects such as telephone poles, but they might also want to measure their height or spacing.

With the well-calibrated device, we have not only a camera, but a precise instrument which can be used to make precise measurements of the world. In terms of the usability of the camera, mobile mapping is again a more extreme and demanding use case than most consumer or professional studio cameras on the market.

Our cameras need to be attached to a car on any continent of the world, rain or shine, and continue operating without interruption, even if the street is bumpy, and even if it’s burning hot or freezing.

The camera needs to be easy to attach to the car, yet very safe; no one wants to be in a car accident, but accidents can happen and the camera needs to stay attached even in the worst circumstances.

The camera does have things connected to it, including the battery, the gps antenna, the ethernet cable, as well as perhaps an auxiliary cable to attach other devices such as the Riegl or the Leica Pegasus, or other lidar devices.

We won’t lay out our roadmap here, but I’m happy to say that we are incredibly excited to release new products which take high-resolution imaging and scanning to a new level.

In Conclusion…

Designing products is a difficult and iterative process, best initiated in their conception by a somewhat unusual user with a somewhat unusual problem, who wants more than anyone else to solve it. It requires a very careful understanding of the state of the technology and how something can be designed.

Version 1 won’t be perfect, but at least it should work better than what’s out there. After that, hopefully the designers and engineers are as close as possible to the users, in order to see and understand what should be improved.

This is what we are doing right now in Prague at Mosaic. We’ve proven that by

- Properly researching and listening to customer demands

- Finding the gap in the market

- Dedicating the unimaginable effort to design and prototyping

- Keeping that focus and saying NO to some tempting things along the way

It is possible to design a solution that customers will love to use because it really, truly solves their problem(s).

Stay tuned for part 2 of this mini series where I break down the technologies behind Mosaic cameras and what have made them the new industry standard for high quality data collection in the mobile mapping industry.